High-tech talent flows back to India

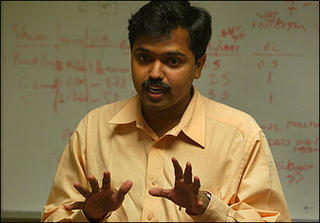

Pavan Tadepalli, of the outsourcing firm Sierra Atlantic, has decided to return to India. He may be the bellwether of a trend. (Globe Staff Photo / Pat Greenhouse)

Pavan Tadepalli, of the outsourcing firm Sierra Atlantic, has decided to return to India. He may be the bellwether of a trend. (Globe Staff Photo / Pat Greenhouse) Those who helped fuel US boom may spur brain drain

Tadepalli turned it down, and chose to return to India.

''There are more opportunities in India now," he said. ''What I can do in Boston, I am confident I can do the same thing in Hyderabad."

The lure of a career in the United States, especially in technology, proved irresistible to India's best and brightest engineering graduates through the 1990s, and even as recently as a few years ago.

But with the maturing of the US technology industry, and the rapid expansion of India as a center for software programming and business process outsourcing, thousands of Indian engineers and managers -- many of them US-educated and working on Route 128 or in California's Silicon Valley -- are opting to go back to their homeland.

The trend is raising fear of a brain drain. Some business leaders are worried that the immigrant Indian entrepreneurs who helped fuel the US technology boom might now start companies in India, and take whole classes of jobs with them.

''It could deplete the stock of educational and scientific talent that we have here," said Alan Tonelson, a research fellow for the United States Business & Industry Council, a Washington trade group for small and midsized manufacturers.

American-educated graduates from other countries, from Israel to Taiwan to Ireland, also have launched companies in the United States. But the Indian connection is unique because of the intense engineering focus there.

And returnees starting businesses in India, unlike those in smaller and richer countries, can tap into a large and growing domestic market, and into a pool of low-cost skilled workers.

For some Indians, the reasons for the exodus are personal. Returning expatriates may have aging parents, or they may want their children raised in the Indian culture. But with the explosive growth of India's economy, cities such as Bangalore or Hyderabad increasingly are seen as new magnets for ambitious technologists -- offering an intoxicating mix of hefty raises, multiple job postings, and rapid career advancement, no longer the norm in Cambridge or in San Jose, Calif.

Joga Ryali worked in Silicon Valley for 22 years until he got an offer this year to run the Hyderabad product development center for Computer Associates, the computer software giant. He started there in June.

Tadepalli's employer, the Indian outsourcing firm Sierra Atlantic, sent him to Boston in January to handle the merger with Sceptre Database Consultants, a Westwood company that was acquired by Sierra. By April, he had trained Sceptre employees in new technologies, worked with US customers, and set up processes enabling him to manage projects -- from India. ''We established good communications," Tadepalli said. ''Now we can do it by phone or e-mail."

Neither the US nor the Indian government keeps count of how many Indian employees have left the American workforce to return to India. The Economic Times, a business publication in India, estimated this summer that 35,000 have returned to the largest Indian high-tech center, which is now in and around Bangalore.

That is still a small fraction of the approximately 2.4 million Indian residents of the United States, a number that includes Indian-born residents as well as US citizens of Indian heritage. Massachusetts is home to an estimated 65,000 Indians.

The reverse migrants are a diverse lot. They include those who have graduated from American schools and return to India for their first jobs, and those who retire in India after spending their work lives in the United States. Many do business in both countries but still live in the United States, while some commute between homes in both countries.

Returnees say that India's substantially lower average wages are more than offset by its dramatically lower cost of living. And with the proliferation of Western amenities, from air conditioning to consumer electronics to shopping malls, the returnees say they have found that the American lifestyle is now available in India -- at least for professionals laboring in the gleaming high-tech office parks of Bangalore and Hyderabad.

The impact of the exodus on the US economy is just starting to be felt. When he ran Taral Networks of Lexington, a wireless software company, two years ago, Vinit Nijhawan was surprised that ''one of my competitors came out of nowhere from India." With the emergence of a new generation of US-trained Indian entrepreneurs, ''you can't be complacent about this any more," Nijhawan said.

Some business people say the trend will help both countries, though skilled American workers will have to adapt to new roles.

''The US is still going to be the idea lab and the funding lab, but the experiments will take place in India," said Upendra Mishra of Waltham, chairman of the US-India Chamber of Commerce and publisher of the Indus Business Journal and India New England newspapers. ''Then they'll bring the technology back to the US."

Gururaj ''Desh" Deshpande, a cofounder and chairman of

Businesses that operate in both countries can sometimes benefit by accommodating employees who want to return to India. But there can be a downside: Once they have moved workers back to India, companies find it tougher to retain them in the competitive job market, said Marc Hebert, executive vice president of Sierra Atlantic, which operates in Fremont, Calif., and Hyderabad.

''This is something new," Hebert said. ''Three years ago, these retention problems didn't exist."

© Copyright 2005 Globe Newspaper Company.

1 Comments:

A wonderful artcle.a great blogin general

Post a Comment

<< Home